An interview with Hal Barwood

A chat with the eclectic artist behind the best Indiana Jones in videogames

(Cliccate qui per la versione in italiano)

by Diduz

I can think of two reasons why Hal Barwood deserves your attention. If you love Indiana Jones and games as much as I do, you'll be glad to realize that Hal has been Indy's best adoptive-father in videogames: remembering Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis (30 years old in 2022!) is a given, and dismissing Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine (1999) could be a crime. But that's just a part of the whole story, because there's a second reason to admire Hal: after his strong career in movies, he had the strength to reinvent himself as an accomplished game designer. In the process, he never gave up his faith in storytelling, linear or interactive.

When you joined Lucasfilm Games and "SCUMM University", your background and experience were very different from your colleagues'. How did you fit in that group of people? Did they accept you right away? Were they curious? Did you ever feel out of place for a while?

I had spent like 10 years overlapping with my movie career prepping for a hoped-for game gig. Lucasfilm Games (soon LucasArts) knocked on my door, and I opened it. As to software chops, I had already done quite a bit of coding, including an Apple II RPG in 6502 assembly language. So SCUMM University wasn't a showstopper -- SCUMM was written as a C-style language, pretty familiar territory. What was tricky was feeling out of place. Everyone around me was a generation my junior, and I often felt like an old man. Eventually I made friends in the company -- all people my kids' age. That was kind of strange: I would behave with them as my peers, whereas with my kids, it was, "don't talk to your mother like that."

I found three funny credits for you in some games you didn't actually work on: "Special Guest Film Director: Hal Barwood" (The Secret of Monkey Island), "Opening Fixed by Hal Barwood" (Day of the Tentacle), "Said it was a good idea: Hal Barwood" (Full Throttle). Are these just plain jokes or are there some interesting stories behind them?

You know, I'm not that shy professionally, and maybe I offered a suggestion or two that either was or was not well-accepted. Those credits look kind of aggressive to me now, but of course, they're also just playful.

Is that you, wrapping up The Secret of Monkey Island boxes?

[picture credits: Oldgamesitalia]

Yeah, management told us we had to recognize a shipped product in our accounting by the next day, so a lot of us stayed up all night practicing a different feature of game development in those days -- packaged goods. Egad. Shows how amateurish our business was thirty-odd years ago.

Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis is a sequel to the movies, but it's also a sequel to the previous Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade - The Graphic Adventure by Ron Gilbert, David Fox and Noah Falstein (who designed Fate with you). I suppose you used that as a foundation for Fate of Atlantis: what did you like of the previous point & click game? What did you want to modify or improve?

This question can't be answered in a few sentences. I wanted to at least make a game that was a worthy successor, but of course I had ambitions as well to go beyond. I was grateful for the SCUMMlords' development of 3D character movement, and for the icon-based verb UI. I added action-adventure elements (camel racing, balloon riding, etc.) Beyond that, I invented a wider range of puzzles, cooked up an original story that seemed to fit, and contrary to SCUMM Law -- Indy, that daredevil, was allowed to screw up and die.

The three-paths structure in Fate of Atlantis was a great idea, gameplay-wise. Considering nowadays adventure games rely more heavily on story paths, I'm curious to know your take on the effect this decision had on the narrative of Fate. E.g., I chose the "team path" the first time I played the game, so that became "canon" in mind. I came back to complete the other paths, but I couldn't help to feel them as "retcons", in a way.

My co-designer and (now) old friend Noah Falstein thought up the three paths that kept me up all night for months on end making them work. Noah knew from feedback on Last Crusade that our players had varied taste, and he wanted to accomodated all of them. However, only the completists really wanted all three paths. And even then, they re-use several elements in differing ways, and they converge when the player arrives in Atlantis. Ahh, the costs, the time. *sigh*

To me Sophia Hapgood is the best female character in the Indy universe after Marion Ravenwood. There's an echo of Marion, but she's still unique and funny. You made her not only important in the story, but even controllable in some sections of the game. Was that always the idea? Did you create her to have a secondary character to control?

Thanks for the kind remarks about Sophia. Yes, Noah and I both wanted the multi-avatar featurette. But she's important because I wanted to tell a real tale, tall as it was.

I understand you were the main (if not the only) dialog writer on Fate of Atlantis. How did interactivity and dialog trees affect your traditional screenplay-oriented approach to writing? Did you code dialogs yourself? Ron Gilbert often said he created the SCUMM Story System also to open game programming to people who weren't "born coders". Theoretically, a SCUMM script had to be readable almost as a movie script. Do you think his goal was achieved?

I did write most (indeed, not all) of the Fate dialog. Because of the multiple-choice format, a form of word puzzles, there's around three-X amount of chatter than minimally needed to tell the story. The system did encourage players' imaginations as they considered the alternate choices; an enrichment you don't find in a movie where severe dialog compression is essential, but sometimes do in books, which are more expansive, and within which ideas can be batted around some.

SCUMM scripts are pretty abstract, but then, to a naive reader, so are screenplays.

Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis was the second LucasArts adventure game to feature iMUSE, providing a continuous and adapting musical score. Did you have a lot of input on the musical texture of the game? How did you work with Michael Land, Peter McConnell and Clint Bajakian?

I love those guys. They are all super-smart, all artists and coders, all among the adults in the room, and all of them willing to answer my infinite supply of naive musical questions. They were working on iMuse, interactive music, where the tempo or mood of game situations that changed with player input would trigger musical adaptations. Some of the effects were subtle and nobody even noticed them. The one thing that really worked in Fate was a drum beat that came on when Indy moved and dropped out when he stopped. The result was propulsive and then eerily thoughtful. And really simple-minded; not quite the intricate interplay they had in mind, I guess.

To me, your precious work on Indiana Jones at LucasArts made the character independent from Harrison Ford. Recently Lucasfilm announced that their classic characters won't be recast, so the fifth Indy movie could be the last one! You've already proved Indiana can exist beyond Harrison: do you think another actor could portray Indiana on the silver screen?

Oh sure, and if Disney sees enough money dancing in their imagination, it will happen. Make Indy younger, or just move on. Dr. Who and 007 haven't had any problems.

In the Nineties, between Fate of Atlantis and the Infernal Machine, you designed smaller games such as Indiana Jones and His Desktop Adventures and Yoda Stories. Procedural games are very common these days, but I still think those "casual" titles were unique, because you experimented with procedural storytelling, which sounds like a sure headache to me! What was you design strategy to create them?

I hate long games. Grinding is boredom, the thing itself. In those bygone days at LucasArts, games cost a lot of money and companies (not only LucasArts) felt an obligation to deliver value for their customers' money. I wanted a rich experience, but one that could be broken up into short chunks complete unto themselves, and then available for replay. So I invented a genre of "casual game" before the term existed. Nobody else in the company had the slightest interest, so to prove my ideas I built a prototype in f-ing HyperTalk on an f-ing Mac Classic just before its screen died. I still love those things, especially Yoda Stories, which was an evolution in design. We should have made more of them.

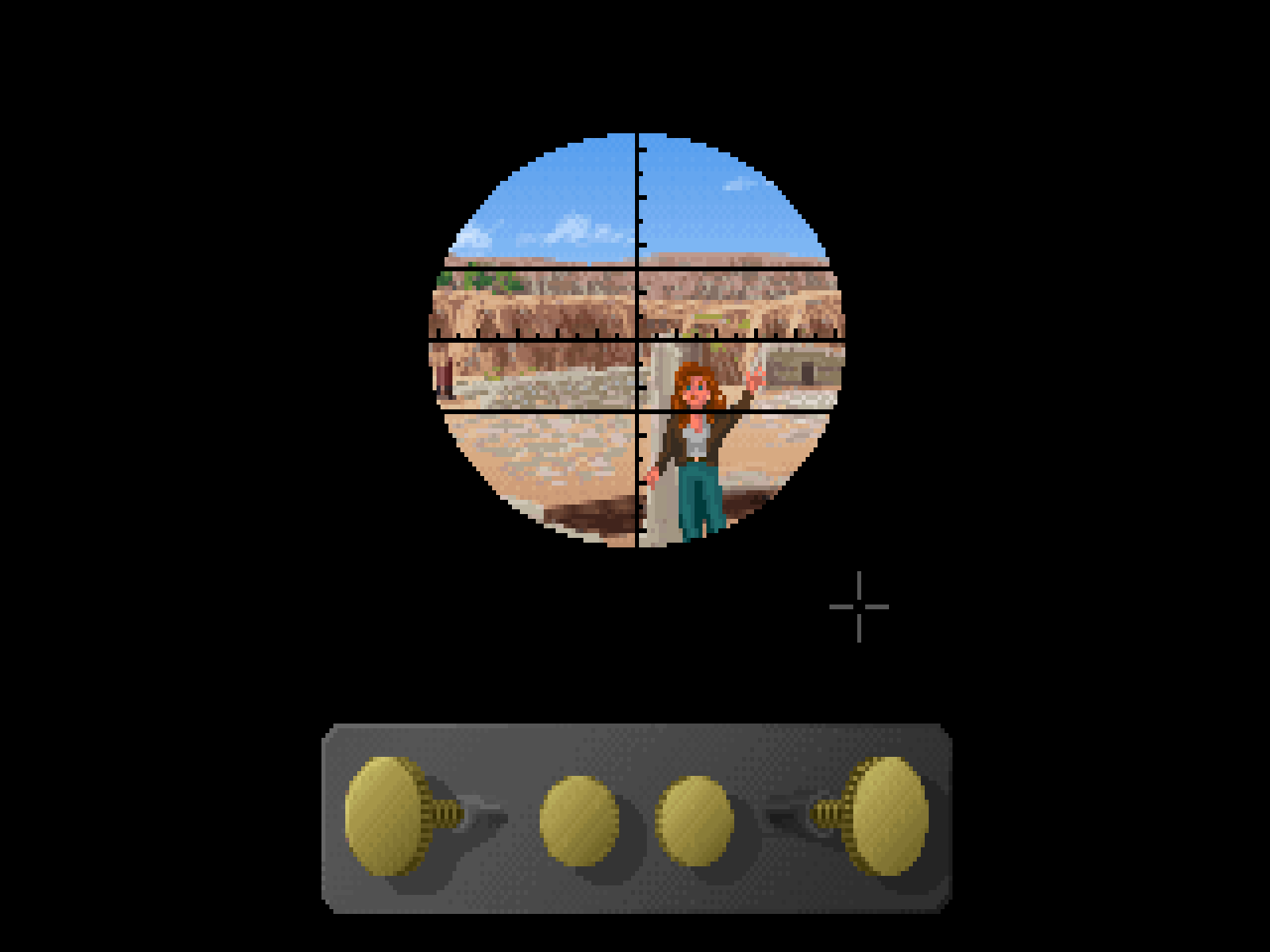

In Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine (an incredibly underrated game, IMHO) Indy faces elements that can be considered "almost sci-fi". This is risky territory for a franchise which began with a quest to get the Ark... and yet, managed by you, that angle worked much better than it did in Crystal Skull. What was your recipe to bend the franchise... without breaking it?

Just to make sure my geek passport is in order, be it known that I, like many of you, loathe Crystal Skull. I think it got in trouble because the MacGuffin / ancient artifacts that form the underlying platform are entirely sci-fi from the get-go. Why not Roswell? There you've got some history at least. Instead, Infernal Machine starts with an excavation of a real and famous archeological site, and the MacGuffin that emerges is Biblical. Then it bends into fantasy and horror. (As do the movies -- think what comes out of the Ark!)

I also wanted to ditch the Nazis, those goose-stepping, Sig-heiling morons, and move on. Commies ... why not?

I've always considered The Infernal Machine complementary to Fate of Atlantis. The latter feels more like a movie, whereas Infernal Machine is more along the lines of an... "Indiana Jones simulator"? If I'm making any sense, did you consider this difference while developing Infernal Machine?

I lost interest (temporarily) in adventure games as soon as I finished Fate. The games that I enjoyed were all action-adventure, with lots of combat. Infernal Machine was the result of my itching-for-action sensibility.

Footnote: on Infernal Machine replays I have managed to kill two hundred or more Russkis on my way to victory. Sheesh. I would design differently now.

I loved the large, explorable levels in Infernal Machine, and I loved the urban locations of Fate of Atlantis and its cast of characters. Do you think an Indiana Jones game could ever combine these two souls in one game?

Oh yes. Grand Theft Jones!

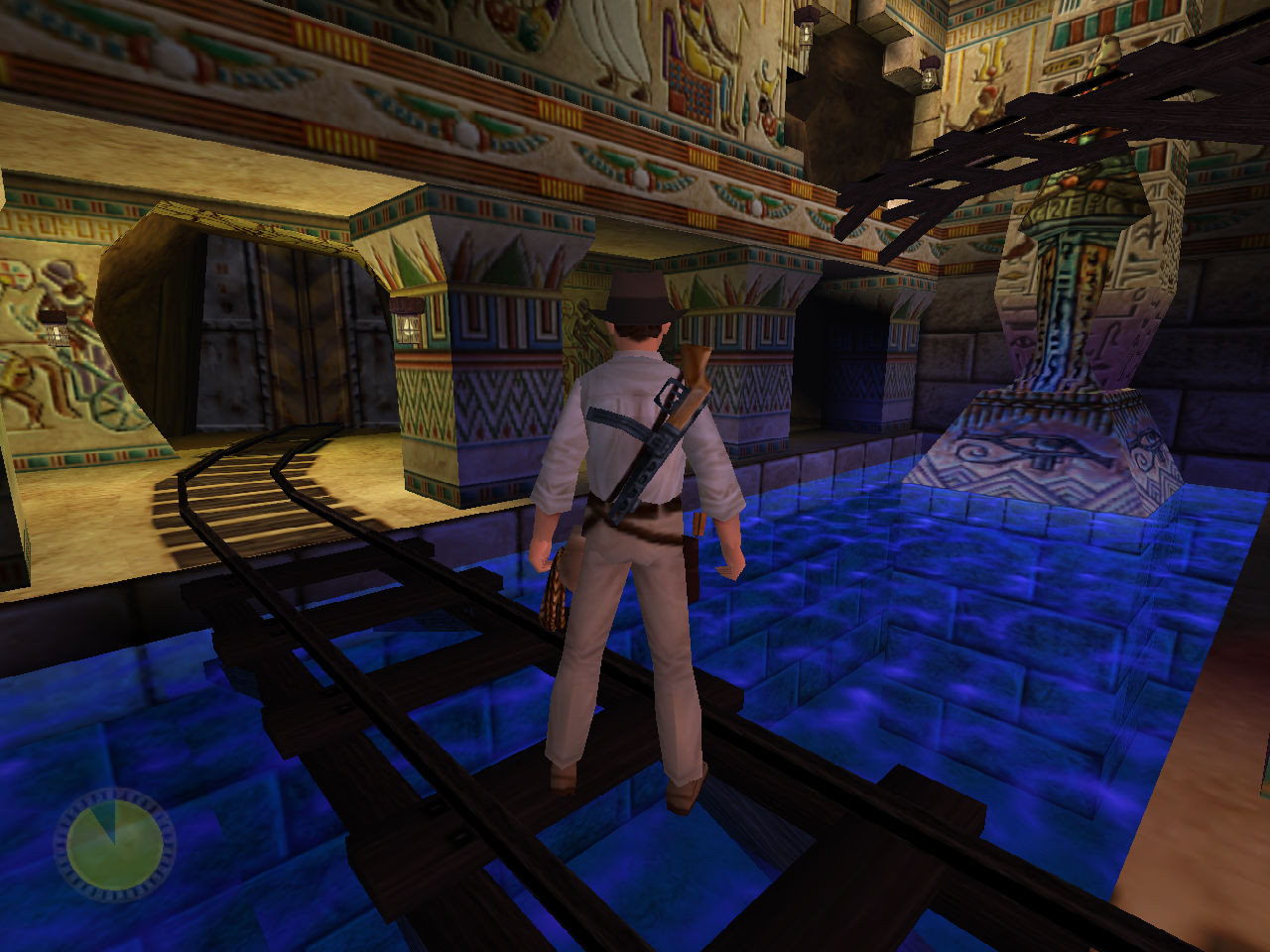

I'm sure the advent of 3D in videogames had to be particularly interesting for a filmmaker. How did the director and the designer in your mind interact (or clash!) during the development of Infernal Machine and RTX: Red Rock?

Interesting doesn't quite say it: 3D game construction is hard work. I love stories, love narrative, and I designed both games with levels as chapters. An open world might have worked better -- especially commercially -- who knows? But these elevated questions of aesthetics give way to the practical horrors of pushing pixels. Building the engines for these games took forever (we should have bought them from third parties). On Infernal Machine we could display maybe 5000 polygons a frame. On Red Rock it was more like 25,000. Not enough, and my attention to design got sidetracked by the difficulties of production. But I've mellowed. What looked like crap to me for years now just seems pleasantly retro.

I'm curious about the Hal Barwood games that never were. In my research I read about three projects that never went into production: 1) An interactive movie running from VHS tapes (!!!), in the late Eighties; 2) A full-motion-video adventure game called Rapid Transit; 3) A Star Wars adventure game, The New Emperor. Could you briefly describe those projects? What were their strong points?

VHS tapes -- could have worked. Dragon's Lair was a very similar idea with Dirk the Daring leaping from track to track as the laser disc (and later DVD) sped along unimpeded. (Interesting sidebar: the Dragon's Lair logotype was stolen from David Bunnett's logo for my movie, Dragonslayer.)

Remember that brief moment in history when the term, "multimedia" meant something? I wanted to do adventure games that were a little more fluid than they had been. Rapid Transit was like that. It involved a BART train that disappeared into another dimension under San Francisco Bay. New Emperor was my way to carry the Star Wars universe forward in time, instead of backward. C-3PO would have been the avatar -- perfect! Each of those games would have advanced the art, but sales of our adventure titles at the time were dismal, so they never got made.

You've been writing novels for the last ten years or so. You've always been a writer, so I don't think this is exactly a stretch for you... and yet...how did you adjust to create entertainment WITHOUT visuals, which informed the vast majority of your career?

Well, I still design and produce all my covers! But more seriously, when deprived of actual imagery, the idea of the written word is to stimulate the mind of the reader. I think the essayist John McPhee put it well: "The reader is the creative partner. You just throw half a dozen images up there and the reader paints the whole canvas."